Vaca Muerta da Argentina enfrenta desafios

jan, 15, 2019 Postado pordatamarnewsSemana201903

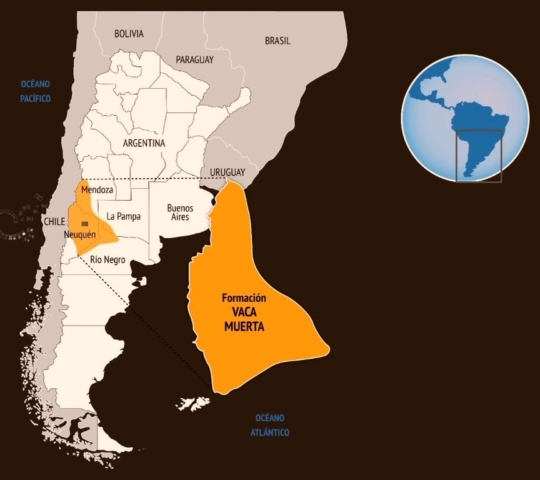

O potencial de crescimento do Vaca Muerta Shale Play na Argentina poderá ser prorrogado por gargalos logísticos específicos do local, medidas de austeridade do governo e altos custos de produção.

Por outro lado, a Argentina pode encontrar no Vaca Muerta o avanço necessário para reanimar sua frágil economia. Até aquí os campos já atrairam US$ 165 bilhões em compromissos de investimento de alguns dos principais participantes do setor, como Chevron, ExxonMobil e Total. Segundo a Secretaria de Energia da Argentina, o Play poderia dobrar a produção de petróleo e gás do país para 1 milhão de barris por dia em 2023, potencialmente transformando o país em um exportador de petróleo com capacidade de exportação superior a 500 mil b/d de petróleo e de 80 milhões de m3/d de gás.Especialistas sugerem que o país deve garantir suprimentos adequados e oportunos de areia fraturada, que atualmente é transportada por caminhões de minas localizadas entre 600 km e 1.400 km de distância. O governo está se preparando para convocar uma licitação para cortar custos logísticos, embora as partes interessadas possam ser desencorajadas pelas atuais taxas de juros de 60%. De qualquer maneira, o governo nacional está preparando o concurso no valor de US$ 780 milhões para conectar o Play ao Atlântico.

Fontes usadas:

Outlook 2019: Argentina’s Vaca Muerta faces bottlenecks that could slow growth

Buenos Aires — The Vaca Muerta has attracted $165 billion in investment commitments as companies like Chevron, ExxonMobil and Total bet on the production growth potential of Argentina’s biggest shale play, but bottlenecks are emerging that could limit a ramp-up in activity.

Laurens Gaarenstroom, general manager of unconventional ventures in Latin America for Shell, said companies must work on reducing costs over the next two to three years to show that “real money” can be generated out of the play. That will help attract capital to Vaca Muerta that otherwise could go to US plays, where costs are lower and the economy more stable.

The key is to cut costs for fracking, logistics, proppant and services to drive the breakeven price well below $40/b.

“We still need to work on these cost elements to really take off,” he said.

At the same time, the industry must prepare for a surge in activity by beefing up the availability of human capital and services.

“Are we going to be ready for that?” Gaarenstroom said.

This is on the minds of many oil executives — and government officials — as they look to Vaca Muerta to not only make Argentina self-sufficient in energy after years of import reliance, but a net exporter.

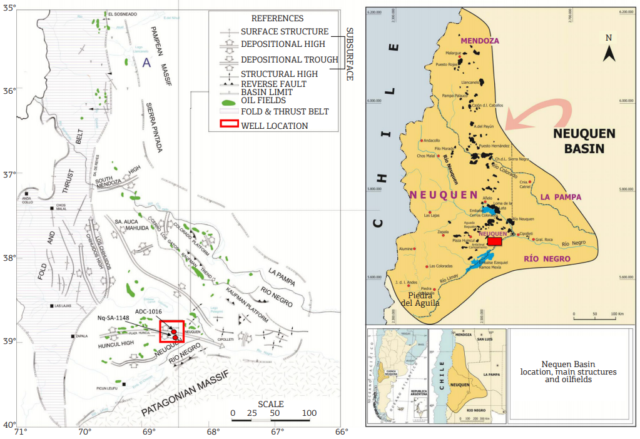

The Energy Secretariat estimates that the play, which runs under largely unpopulated flatlands in the west, could lead a doubling of oil and gas production to 1 million b/d and 260 million cu m/d, respectively, in 2023. That would allow exports to surge in 500,000 b/d of oil and 80 million cu m/d of gas that year, and continue to grow.

SOURCING SANDS

The challenge, of course, is to make this happen, and already companies are warning of bottlenecks.

One is the lack of a local source of sand for fracking proppant. The supplies are delivered by truck from mines between 600 km and 1,400 km away, boosting logistics costs.

The national government is preparing a tender for a $780 million, three-year project to expand a railway to the play from an Atlantic port, which would help cut well development costs by 5% to 10%, according to Daniel Dreizzen, the country’s secretary of energy planning.

However, it is uncertain how long the project could take, given the country’s economic and political instability. After a 100% devaluation of the currency in 2018, the central bank raised interest rates to more than 60%. This has made it harder to finance projects, and could deter companies from bidding next year in the railroad tender.

Ryan Carbrey, senior vice president of shale research at Rystad Energy, a consulting firm, said the railroad “may not be completed and usable in five to seven years.”

Also, the depth and high pressures of Vaca Muerta wears down drilling equipment fast, pushing up costs, Carbrey said.

The pressure pumpers “are not getting the margins to be profitable and stay in business,” he added.

Indeed, Argentina-based San Antonio International recently sold its business to Texas-based Lone Star due to the low margins.

“Vaca Muerta will not have the exponential growth at least in the next few years that we have seen in the US,” Carbrey said. But if the bottlenecks are resolved, “we do expect high potential for Vaca Muerta.”

In the meantime, Gaarenstroom said: “We have to make it work.”

PROJECTS IN THE PIPELINE

Shell is preparing its first full-development project in the play’s oil window, with a target of ramping up production to 42,000 b/d over the next three years.

Others are poised to follow suit. Omar Gutierrez, the governor of Neuquen, home to much of the play, said 30 projects are in the pipeline, building on the four in mass development. In total, companies have committed $165 billion in investment, he said.

The early development has taken the play’s production to 70 million cu m/d of gas and 125,300 b/d of oil, driving up the Neuquen Basin’s total production by 9.5% for gas and 10.5% for oil in 2018 on the year, Gutierrez said.

With the 34 projects accounting for only 27% of the play’s acreage, he said the production and export growth potential is large.

The challenge is to get past the bottlenecks.

Carlos Ormachea, CEO of Argentina-based Tecpetrol, which is in full-scale production on a $2.3 billion gas project in the play, said the pace of its next development will be slower because of the midstream bottlenecks and high costs, which he estimates as 20% more than in the US.

While Tecpetrol can improve execution and management to shave costs, the costs of moving water and proppant must come down with investment that is out of its control, he said.

Argentina’s government wants to make this happen, but it is trying to balance the fiscal deficit in 2019. This is limiting how much it can invest in infrastructure projects, meaning that the next few years may be a slog for companies in the play.

But in the longer term, Dante Sica, the country’s minister of production and labor, said that as more companies start up projects, this will bring economies of scale to lower costs.

“The more operations you have, the more efficient it is, and this helps to bring down costs,” bolstering profits and attracting fresh investment, he said.

But to reel in more companies, Argentina has to fight against its own past of nearly 100 years of economic and political volatility that came to the fore again with a financial crisis that started in April 2018 and may run through a good part of 2019.

“It will take time to rebuild confidence,” said Federico Tomasevich, president of Puente, a leading investment bank in Argentina. “We need to be able to learn from our mistakes to not repeat them again. This is the big challenge for the government. Otherwise we will be always discussing the same problems.”

-

Regras de Comércio

ago, 28, 2019

0

Acordo entre Mercosul e UE está em revisão jurídica, diz secretário

-

Portos e Terminais

jun, 06, 2023

0

Porto de Itapoá bate o próprio recorde de movimentação pela segunda vez em 2023

-

Grãos

dez, 29, 2023

0

Como a China tem cortado o consumo de soja para depender menos das importações

-

Economia

fev, 07, 2024

0

Volume compensa queda de preço na exportação brasileira